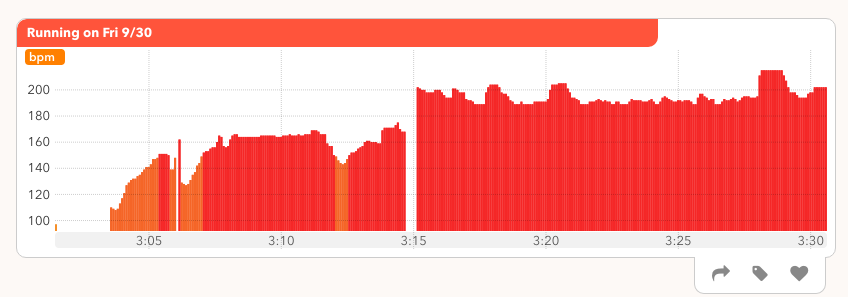

Imagine going out for a run with your Apple Watch, seeing your heart rate spike to 200 beats per minute—and having it spiral up even after you stop running.

That’s what happened to Matt [1]. When he called an ambulance, he found it he had an abnormal heart rhythm called supraventricular tachycardia. Each year, about 795,000 people are hospitalized for abnormal heart rhythms in the US, and along with atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter, SVT is one of the most common arrhythmias.

What follows is a brief interview with Matt, his heart rate chart during the run, background on what causes SVT, and how SVT is different than a heart attack.

Important note: the Apple Watch is not a medical device. Although we and others are working to develop algorithms to detect abnormal heart rhythms as part of the mRhythm Study with the UCSF Health eHeart project, these efforts are in the research phase, and not yet ready to be used for treatment or diagnosis.

What was running through your head as you decided whether to call an ambulance?

Matt: My wife had ran home and at that point it had been racing for well over 15 minutes. I was more worried about my wife than anything. I don’t know what a heart attack is like, but I wondered if this might be what one is like.

In contrast, abnormal heart rhythms are caused by electrical problems within the heart. In every normal heart beat, electrical signals travel from top to bottom, starting with the pacemaker cells, through the atria, the AV node, and then ending in the ventricles (the bottom two chambers of the heart). SVT is caused when the electrical signal travels backwards through an “accessory pathway”—an extra piece of tissue that conducts electrical impulses—forming an electrical loop within the heart. Since the loop is shorter than the normal top-to-bottom pathway, it acts as a “short circuit” that causes a fast heart rate.

“I don’t know what a heart attack is like, but I wondered if this might be what one is like.”

You were running when your heart rate raced past 200. When did you first notice something was off? Did you feel anything in your chest, or did you realize it just from your Apple Watch heart rate data?

Matt: You can definitely tell when your heart is racing at 200 bpm. I usually top out at 168 when I am really pushing myself (not an athlete). We had stopped after a warm up jog (140 bpm), so my wife could stretch. Normally my heart rate would begin to go down but it began to spiral up. I knew then that I was having an episode and then began thinking about a spot I could lay down and put my feet up if it didn’t slow down. Having my watch simply meant that I could see a visualization of it.

When the ambulance came, what tests did they run and what did they tell you was going on?

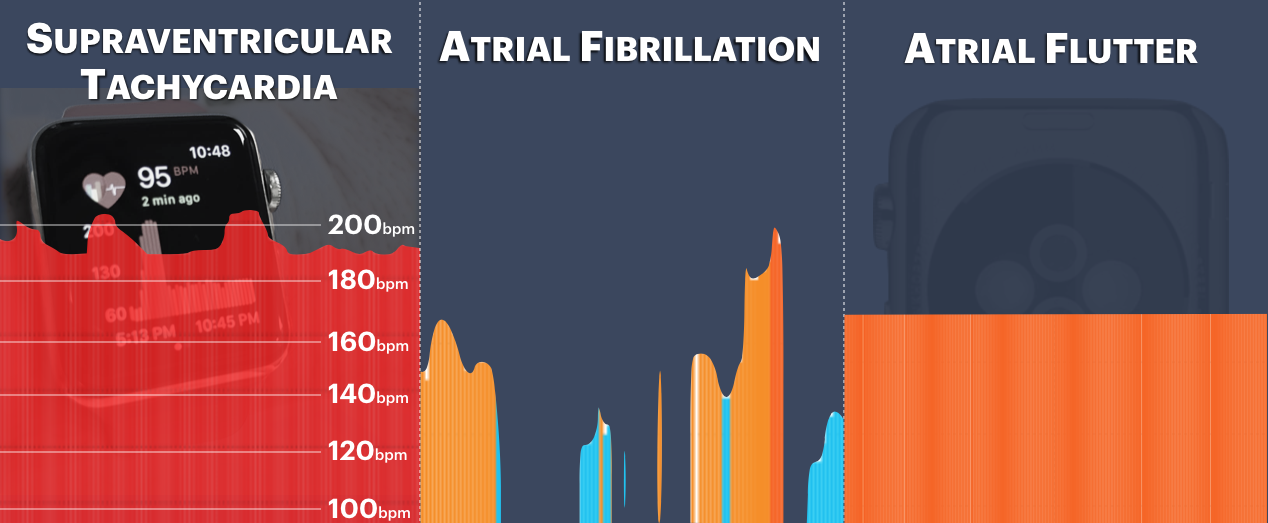

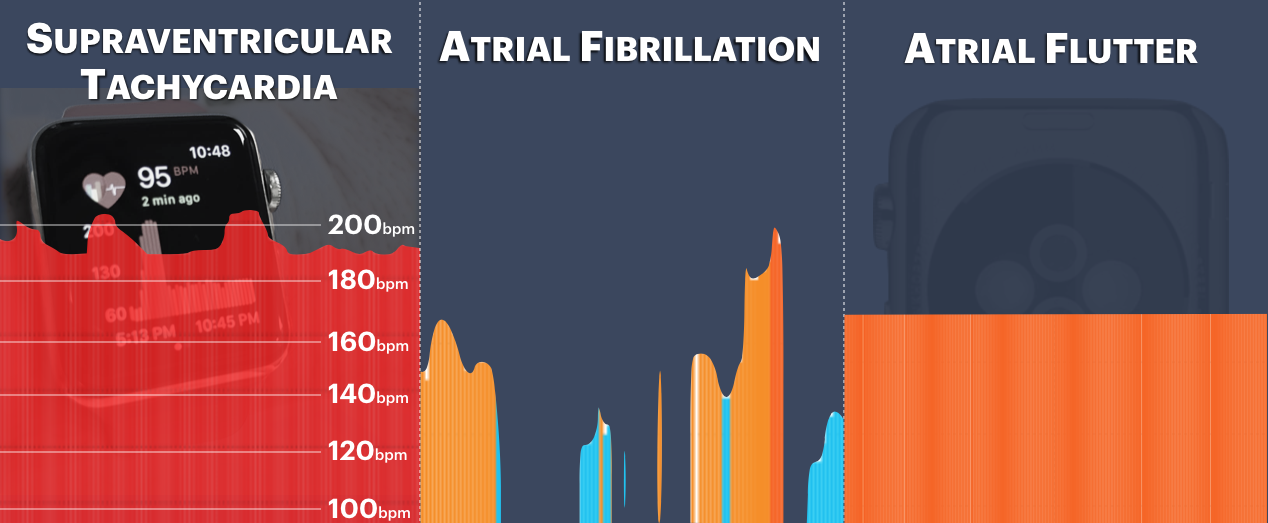

Matt: They immediately diagnosed it. They first asked me to strain like you need to go to the bathroom because that constriction of muscles can help your heart reset. There are several “tricks”. Apparently I just figured out the first one intuitively (laying on my back with my feet up). They did an EKG then put sticker paddles on just in case and then administered a drug to briefly stop my heart intravenously. Cardiac electrophysiologists traditionally use an EKG (electrocardiogram) to measure voltage inside the heart, which gives them detailed diagnostic data for each heart beat. The Apple Watch’s heart rate sensor is a PPG (photoplesmography), which gives information on the heart rate only. Nevertheless, you can often tell the differences between different rhythms using heart rate alone. Take a look at the three examples from the top of this page again:

What do wearables mean for the future of medicine?

Matt’s story isn’t the only example of somebody discovering a medical condition through Apple Watch. People have discovered third degree heart block, abnormal blood clots, rhabdomyolysis, sick sinus syndrome, atrial fibrillation, and even what happens to your heart after a breakup.

In order for wearables to save lives at scale, we’ll need rigorous clinical validation that the sensors and machine learning algorithms to detect conditions are accurate. We and others are working on this. If you have an Apple Watch—regardless of whether you have a heart condition—you can help by signing up at our research page or from within the Cardiogram app (the “Me” pane).

Have you encountered a situation similar to Matt? Feel free to share your story in the comments or email me directly. I’d love to hear from you!